Intertidal invertebrates are the soft-bodied and shelled animals that thrive along our estuaries and coastlines. This diverse group includes familiar species like crabs, starfish and sea anemones as well as lesser-known creatures that hide in rock pools and that can be found scattered along Devon’s sandy shores.

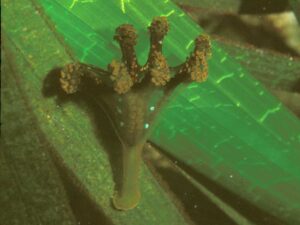

Bright orange sponges cling to the undersides of rocks, while translucent, globular sea squirts glow from shadowy crevices. Delicate and charismatic sea slugs glide through seaweed, grazing on whatever they can find. Shells appear in every shape and size, from tiny hydrobia that are just a few millimetres long and are vital for wintering birds, to dense beds of mussels and oysters that form rich habitats teeming with marine life.

Important habitats for these species include:

Rocky shores provide a mosaic of microhabitats for intertidal invertebrates. Crevices, overhangs and shaded rock pools offer shelter from drying out and predators. Barnacles, limpets, chitonsA chiton is a small sea creature that lives on rocks along the seashore. and sea slugs are commonly found clinging to rocks or grazing on algae, while sponges and tube worms anchor themselves in more protected spots.

Though seemingly barren, sandy shores host burrowing invertebrates such as lugworms, razor clams and sand hoppers. These species play a vital role in sediment turnoverThe mixing and movement of sand by animals as they burrow and feed. and nutrient cyclingThe process of nutrients being moved around and reused in the sand by animals and other organisms.. The shifting substrateA surface or material than an organism lives, grows or feeds on. also supports mobile scavengers and filter feeders that emerge when the tide changes.

In sheltered estuarine zones, dense growths of seagrass and seaweed provide excellent cover and feeding grounds. For example, unlike their free-swimming relatives, stalked jellyfish have a stalk they use to attach themselves to seaweed or seagrass.

The LNRS has identified 15 intertidal invertebrates as Devon Species of Conservation Concern: five molluscs, two worms (annelids) and eight species of cnidaria (sounds like nih-DARE-ee-uh). Cnidarians are a surprisingly diverse group, with around 12,000 known species; three times more than mammals. They include familiar creatures like jellyfish, corals and sea anemones as well as lesser-known species such as hydroids.